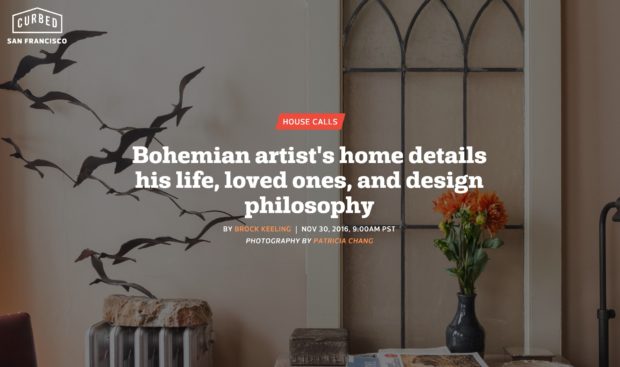

The architectural site Curbed.com featured my San Francisco apartment in their November 2016 edition of House Calls, and interviewed me on subjects of style, design, life, and love. The opening line says it all: “As San Francisco becomes blander, we old-timers have a responsibility to be weirder…” Indeed. Here’s the link.

Category Archives: Blogs

[Insight]: The View From Stage, Before Beethoven, San Francisco Symphony

Bass-baritone Shenyang, before the house lights went down at SF Symphony, June 2013 (Photo: John Vlahides)

The view from stage at the San Francisco Symphony, right before we performed Beethoven’s Missa solemnis, together with 3000 people, who 90 minutes later leapt to their feet. I’ve shared this view before, but each time it’s new—and ephemeral, like high art itself.

I cannot sufficiently express the transcendent joy I experience singing onstage with the San Francisco Symphony and Chorus. Though you’re making the music, producing the sound with your body, there is no ‘you’ in the chord, just this incredible harmony reverberating in perfect precision, up and away, a ship of air carrying beyond earthly static, hostility and strife, to the vastness of the Spheres—place of infinite joy and creative imagination. And so I love to sing—especially with MTT a perfectly tuned Missa solemnis, which Beethoven inscribed ‘from the heart, may it go to the heart.’ From mine to yours, these shows I sang.

Maestro Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT) collaborated with Tony-winner Finn Ross to present Beethoven’s great masterwork in an entirely new way—semi-staged, with video imagery and movement designed to tease out the density of the music, make it accessible to the listener by providing visual cues, literally shining light onto the motifs, themes and expositions. Music this challenging—Beethoven at his most pathological, but also his most loving—demands program notes. MTT, in the following short video, shares his artistic reasoning, with accompaniment by Beethoven.

For more on this production, see reviews in the Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, New York Times, and Los Angeles Times. And now the season is over until September, when I look forward to returning again to this gorgeous hall, and to smiling back at you from stage, ready for take-off.

[Essay]: Why Not to Take Sleeping Pills on Airplanes

Should one take pills to sleep aboard airplanes? I examined this question in an essay I read at Litquake – that great annual literary festival – part of a live reading presented this autumn by 7×7 Magazine, which had commissioned me to write an essay on the subject of ‘travel misadventures.’ The following is a true story.

Two shots of Jack Daniels, 1mg of Ativan, and 10mg of Ambien. This was the cocktail for sleep suggested to me by a medical doctor I once met on a dinner flight from New York to San Francisco. We were seated together in business class, on our second round of cocktails when the subject of jet lag arose, and I asked his opinion about taking sleeping pills on long-haul international flights. In good professional demeanor, he made no specific recommendation for me, as I was not his patient, but he did share with me his own personal prescription, the regimen he himself followed: two Jack Daniels, 1mg Ativan, and 10mg Ambien.

His reasoning was this: the alcohol relaxes, the Ativan compresses time, and the Ambien knocks you out and erases any memory of discomfort. They’re all fast-acting drugs, so by the time you land, you’re fine.

The first time I tested this miraculous cocktail was on a flight to Australia, and I arrived in Sydney feeling great. I stayed true to the formula – 1mg Ativan, 10mg Ambien, but instead of bourbon, I drank champagne – a nod to the special occasion that I still believe flying to be, despite all evidence to the contrary. Alcohol and drugs made flying glamorous again. And though I awoke from slumber dazed and foggy, by the time I reached baggage claim, I felt refreshed and awake. The doc’s prescription worked like a charm, and it became my regular regimen on overseas flights.

Shortly after the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers, during the first months of the financial crisis, I found myself aboard a near-empty Boeing 777, bound from London to San Francisco, with an entire row of five economy-plus seats all to myself. As the flight attendants moved through the cabin counting heads and making their pre-departure checks, one of them – a fit young woman with bright eyes, a spiffy bob hairdo and an easy smile – attempted eye contact with every passenger, most of whom ignored her. I noticed her doing this, and so was ready to make eye contact back at her when she arrived at my seat. She stopped, crossed her arms, stared at me, and said, “You look different from the other passengers. What’s your story? I bet you do something interesting.”

I laughed, then said that I looked different because I was from San Francisco, but she kept pressing, and so I answered her. “I am a travel writer, and I’m on my way home from shooting a documentary in Morocco.”

“Ooh, I knew it! You have my dream job. I want to talk to you. I’ll come get you after my service is finished.”

“Okay,” I said, “but I’m planning to sleep after dinner, so make sure you come back before I’ve taken my pills.”

“Don’t worry. It’s an empty flight. Service will go fast. My name is Sherry. I’ll be back!”

During dinner service, Sherry slipped me a couple of extra bottles of wine without charging me for them. Two hours and one feature-length film later, Sherry still hadn’t returned, and it was time to make my bed. I raised the four arm rests, rolled blankets against the pointy metal seatbelts, and popped my pills. And just as I was clicking my seatbelt over the top of my blanket and pulling my eye shade down over my face, I heard through my earplugs, “I’m finished with my service!”

“Oh, no,” I answered. “I just took my sleeping pills.”

“That’s okay,” she said. “I’ll give you some wine! Meet me in the galley in back.”

I’m a sucker for a party girl, so I unlatched my seatbelt, pulled on my shoes and followed her down the aisle.

We sat on jump seats way at the back of the plane, and as I sipped cheap chardonnay from a plastic cup, wondered how I would keep from falling asleep as we talked. But strangely, the more I pushed past the impulse to sleep, the more energized I felt.

Selfie taken in the lavatory of a United 777, at the beginning of an Ambien blackout. Note the gold pilot’s wings.

Sherry was barely 30, young enough to believe that she might actually land her dream job, and so barraged me with questions about what it meant to be a travel writer: How did you get your job? What’s your favorite city? How can I write for Lonely Planet? I usually avoid this conversation because nobody ever wants to hear the truth – that you only travel occasionally and spend most of your days alone, chained to a desk, craving the company of other people. But Sherry’s gregariousness and wide-eyed wonder had completely charmed me, and my growing buzz lent a singularity to the moment: ours was suddenly the most important conversation of the day, and I wanted to help her.

“Okay,” I said, “What do you write?”

She replied, “Well, I sometimes keep a journal – but I don’t write anything else – but I know all about Europe because I’m always there!”

“Sherry, I hate to disappoint,” I said, “but no publishers will consider you unless you can show them some writing.”

She answered, “Well, that’s okay, I actually have a hard time writing.”

“Me, too!” I said, which made us both laugh, and then she started asking about Morocco.

I can’t remember how the conversation ended, but somehow I made it back to my seat, where I slept the rest of the flight, and had recurring dreams of a little kid who kept trying to wake me up.

I awoke groggy in San Francisco. At baggage claim, I began to develop a headache. Once I finally got home, I took a nap and when I awoke a few hours later, got on the phone with a friend, who asked, ‘How was your flight?’ “Fine,” I said, “Uneventful. I had five seats and slept the whole way.”

I had forgotten all about my conversation with Sherry, until I plugged my new phone into my computer and started downloading my pictures. First came shots from London, then pictures of airplanes at Heathrow, and then – what’s this? – me in the lavatory of the plane, then Sherry and me with some sort of turban on my head, then me on the floor of the galley holding a paper airplane with a kid in my lap! And suddenly, in a flash, it all came back.

After Sherry and I had our conversation about travel writing, I did not in fact return to my seat, but instead stayed with her in the galley. When we started talking about Morocco, I told her that I had just been in the Sahara Desert with Bedouin nomads, who’d taught me how to tie a turban.

I remember her saying, “Show me how!” but I couldn’t because the necessary fabric was checked inside my luggage, down in the hold.

That’s when I said, “I have an idea. Go get me a blanket!” and soon I was fashioning a turban on my head out of a nylon United Airlines blanket. Sherry and another flight attendant – a tall Norwegian-looking woman, like a young Liv Ullmann – watched with fascination as I wrapped the blanket around and around my head, and when I was finished tucking it just right, I said, “Ta da!” and the two of them applauded.

“Thank you, thank you!” I said. “Now, should I run up to the cockpit, bang on the door, and yell ‘Halla-halla-halla! They are killing my people!”?

“NO! NO!” They both shouted simultaneously. “Do NOT do that!!”

“Calm down! I’m kidding,” I said with a cavalier slur. And as I sat back down onto the jump seat, my new smartphone fell from my pocket. Sherry reached down to pick it up, and said, “Does this have a camera in it? We need pictures! You look so cute!”

As Sherry and I mugged for the camera, a handsome young boy, maybe 10 years old, suddenly appeared in the galley, wearing a stripy hooded sweater and a yarmulke. He said not a word, just stood there smiling at us – two pretty young women in crisp blue uniforms, and one middle-aged man with a blanket tied around his head.

“Hello!” I said. He smiled and waved, but still said nothing. I had seen the child earlier as I’d approached the galley. He and his father, also wearing a yarmulke, were crammed into the very last row of economy – the worst seats on the entire plane – and the father had slumped over onto his tray table, head in his hands, looking miserable even as he slept. They were flying from Israel, on their second long leg of travel from Tel Aviv to SFO, via Heathrow.

The flight attendants asked the boy if they could get him something, but he only shook his head. Sherry asked, “Is everything okay?” The boy nodded, but still said nothing. He clearly understood, but either couldn’t speak English, or he was mute. Either way, he never spoke a word.

“The kid is bored!” I said. “Don’t you guys have anything for kids? When I was little, the airlines used to give out all sorts of things – playing cards, coloring books, note pads. Don’t they give you any amenities anymore?”

The Liv Ullmann lookalike said, “I think we may have some wings in first class.” She re-appeared moments later with a bag of plastic pilot’s wings and pinned a pair onto the boy’s shirt, while Sherry pinned another pair onto mine.

“I know what to do,” I said. “How about we make paper airplanes?” The boy nodded vigorously. I glanced at Sherry to gauge her response and she didn’t protest, so I said to the boy: “Quick, go to your seat and grab us two magazines!” And soon we were tearing the covers from the in-flight magazine and folding them into airplanes on the stainless-steel counters, while the flight attendants looked on, smiling.

The galley proved too small a space for the planes to fly right, so I motioned the boy into the aisles of the cabin, where we lanced them back and forth, both of us giggling like mad. It didn’t take long for a passenger to complain. Sherry motioned us back to the galley, and closed the curtain. “Stay here, or you’ll get in trouble.” The boy and I giggled as Sherry wagged her finger. I looked at him, pointed to the blanket on my head, then to the yarmulke on his, put my arm on his shoulder and said, “Who says the Jews and the Arabs can’t be friends?”

Learning from the flight attendant which passengers had complained about our having thrown paper airplanes up the aisle, so that the boy and I could avoid them as we prepared to make another sortie through the cabin.

At last I said, “All right, this has been so fun, but I really have to sleep before we get to San Francisco.” And that’s when I finally went back to my seat and passed out. Several times during the remainder of the flight, the boy came to my seat and tugged on my shirt to awaken me to play again, but each time I only opened one eye and said, “Sorry, I’m sleeping.”

I had forgotten the entire thing – the turban-tying lesson, the Israeli kid, the paper airplanes, all of it. Seeing the images unlocked my memory, broke the spell of amnesia induced by the Ambien. The good doctor had warned me of this possibility, that Ambien could erase your memory, but it had never before happened to me, so I’d considered myself immune.

But as I saw each picture flash upon the screen, it all came flooding back. I’d taken selfies alone in the lavatory to show off my new pilot’s wings. And when Sherry commandeered my phone, she’d shot a dozen images of the two of us, and in all of them I’m wearing a goddamn blanket tied around my head – who needs a lampshade when you can wear a blanket? If I’d ever before been in a blackout, I’d not known about it, and certainly had no photographs to remind me. My bloodshot eyes revealed how totally wasted I actually looked – how could Sherry not have known? Then came a dozen more shots of the boy and me, ending with a series of the two of us lying on the floor of the galley, fighting over whose turn it was to throw the paper airplane. I was mortified.

Now I stick to champagne and only take Ativan if I absolutely cannot sleep, but only half a tablet. I avoid Ambien altogether, unless it’s a really long flight, but I never stay awake once I take the pills. I’ve learned my lesson. But just in case, while I sleep, I always keep my camera-phone in my pocket.

[Advice]: Fantastic Man Interview with John Vlahides

Fantastic Man, that archly posh European men’s fashion magazine, interviewed me for its Spring & Summer 2014 issue, and published under “The Recommendations for This Season” my thoughts on staying awake in formal situations – right beside famed architect Lord Richard Rogers’ thoughts on boxing as physical therapy. I’m flattered and honored to be in such company; it is they, the fantastic.

[Video]: BBC Knowledge Channel, Author Profile of John Vlahides

BBC Knowledge profiled me in this 60-second spot, airing worldwide to promote the Lonely Planet TV series, Roads Less Travelled. The question put forth: Why do we travel? The conclusion I drew: If you can’t laugh, there’s a problem. That’s me on the camel.

(This piece is part of a package that won Gold for Best Television, at the Global PromaxBDA Awards, June 2013. Hats off to Elizabeth Jensen.)

The View from Stage, Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco

The view from stage on a sold-out night at Davies Symphony Hall, in San Francisco, always blows my mind. Here’s how it looked last weekend, right before Semyon Bychkov walked on stage to conduct us in Benjamin Britten’s 1962 War Requiem—a death mass for war itself. Tears were shed. Joshua Kosman, in his SF Chronicle review, called us “sensational.” Next week, I’m performing Handel’s Messiah. Music is humankind’s highest achievement; it goes where words cannot, and transforms souls. Come, if you like Baroque, and we’ll share a moment. I’ll wink hello from stage.

The view from stage, Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco (©John Vlahides 2013)

[BBC Video]: “Australian Experience w/John Vlahides: Uluru, Rock of Ages”

Before I visited Uluru for BBC and Lonely Planet, I thought, What’s the big deal about a rock in the middle of the desert? Then I stood beneath it, saturated in color and surrounded by shimmering silence, and I felt awe. Now I get it. This is a mystical place.

How incredible to imagine that Anangu people, the traditional owners of the land, have been around for 30,000 years, passing down oral tradition from parent to child for millennia. Consider this: when you come across an ancient rock painting at Uluru, the story told in the artwork is as fresh and alive to contemporary Anangu people as it was to their ancient forebears. Locals speak of tjukurpa, the catch-all term for regional law, stories, customs, relationships, and knowledge, which together create the foundation of Anangu society. Herein lies the key to wrapping your head around Uluru, something I only began to do. I wished I’d scheduled an extra day.

[BBC Video]: “Australian Experience w/John Vlahides: Great Barrier Reef”

Snorkeling the Great Barrier Reef is like swimming inside a giant aquarium. But to get perspective on its vastness means also seeing it from the air – it’s the only living thing you can see from space.

Before co-producing and hosting these short films for Lonely Planet and BBC, I had never before ridden in a helicopter. What a brilliant place to experience for the first time the thrill of vertical liftoff! We flew 50 miles from the coast to a landing pad in the middle of the ocean (note my enormous grin as we step out of the helicopter), then shuttled to a floating dive station and snorkeled the reef. Lifeguards and roping kept snorkelers from drifting out to sea, and guides led us to clown fish hiding in anemones, past mountains of coral, with a rainbow of fishes surrounding me everywhere I looked. From the macro to the micro, seeing the reef from above and below changed my perspective on the ocean, and by extension, the entire planet.

Heart Reef, Great Barrier Reef, Australia – note the perfect heart-shaped coral reef, at center

Performing Beethoven’s 9th with the San Francisco Symphony

Next week I’ll have the honor of performing Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, under the baton of Michael Tilson Thomas, at the San Francisco Symphony—and we’re recording it. (Last time we recorded, we won three Grammys.) If you appreciate classical music (well, actually it’s Romantic), I highly recommend you come. It’s nearly sold out, so buy tickets tout de suite. Meanwhile, if you’re curious to know what goes into creating a Grammy-winning recording, here’s a glimpse into the making of our last, Mahler 8. Erin Wall, soprano on that recording, will also be singing the Beethoven program.

Part 2: “Australian Experience with John Vlahides: Kangaroo Island, Haven for Wildlife” [Video]

The second of five short films on Australia that I co-produced and hosted for Lonely Planet and BBC: Kangaroo Island. How surreal to see these wild animals up close—like a safari park, but without fences, people or cars. Incredible.

Kangaroos and wallabies are nocturnal. So many roam this island, and hop across the road at nighttime, that occasionally one gets hit by a car. But here’s the thing that distinguishes locals as good stewards of nature: custom dictates that the driver get out of the car to check the animal; if it’s a female with a baby ‘roo in the pouch—a joey, they’re called—it’s the drivers responsibility to take the joey home, raise it until it’s too big to live any longer as a pet, then turn it back to the wild.

Kangaroos and wallabies are nocturnal. So many roam this island, and hop across the road at nighttime, that occasionally one gets hit by a car. But here’s the thing that distinguishes locals as good stewards of nature: custom dictates that the driver get out of the car to check the animal; if it’s a female with a baby ‘roo in the pouch—a joey, they’re called—it’s the drivers responsibility to take the joey home, raise it until it’s too big to live any longer as a pet, then turn it back to the wild.

I had the pleasure of holding one such joey in my arms. It kicked and squirmed and tried to get away, until I began humming “Brahm’s Lullaby” and rocking it like a baby. The ‘roo quieted right down, and even laid its head against my chest, a moment I’ll never forget.

![Michael Tilson Thomas conducting his semi-staged version of Beethoven’s Missa solemnis, with the San Francisco Symphony & Chorus, with soloists (rear L to R) Shenyang & Brandon Jovanovich, and (front) Joélle Harvey & Sasha Cooke. [Where's Waldo? Hint: Glasses.] ((Photo: Stefan Cohen)](http://vlahidesadmin1.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/SFS-Ensemble-MTT-Beethoven-Missa-Solemnis-Vlahides-1-620x413.jpg)